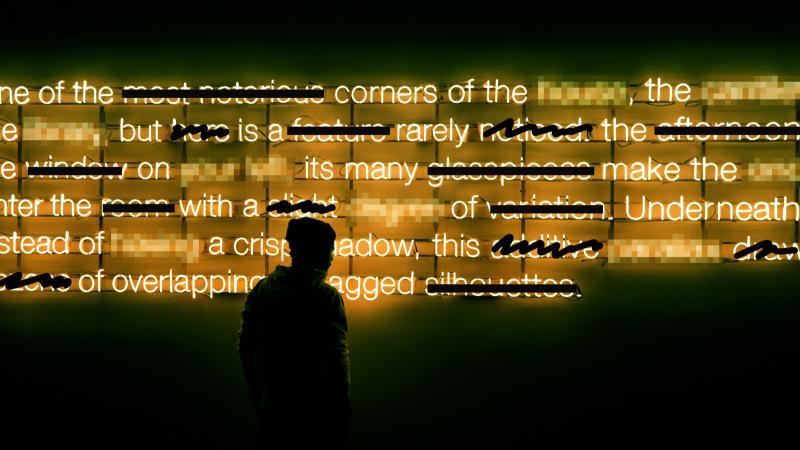

Photo illustration by Mark Riechers. Original image by PNG Design.

Editor's note: This story includes language some may find offensive. We've chosen to leave Mosley's direct quotes uncensored here, in the broadcast, and in the podcast version of this interview. For a censored version of this episode, go here. For a censored version of this transcript, read the WPR.org version.

It hadn't occurred to novelist and screenwriter Walter Mosley that what happened in the writers' room could find its way into a human resources department memo. But when a polite human resources representative called him on the phone to ask why he'd said the "N-word" during a story meeting, he responded, "I am the N-word in the writers’ room."

Later, he wrote about his experience in an op-ed for the New York Times.

At that moment, Mosley realized he was done working in that room — the sense of trust between writers was shattered. He quit the job that same day.

"How can I exercise these freedoms when my place of employment tells me that my job is on the line if I say a word that makes somebody, an unknown person, uncomfortable?" Mosley wrote.

Mosley said true and complete freedom of expression is a key feature of American culture. That means that we might be made uncomfortable from time to time, but Mosley argues that those should be moments of discussion and debate, not an occasion to email human resources.

He spoke to Charles Monroe-Kane of "To the Best of Our Knowledge" about what happened after that fateful phone call, and why no one should have dominion over what words we can use.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Charles Monroe-Kane: When you got that phone call, how did you feel?

Walter Mosley: It's kind of surprising to hear somebody who probably was a white person, who definitely represented an institution run by white men, calling up a black man and telling him that he can't refer to the language that suppressed him and his for four centuries.

I thought "Wow, that's crazy."

And then as I thought about it more, I said this is attacking everybody — it's not just me. It's an attack against the freedom of speech — all of a sudden there's somebody in your office somewhere who can say, "If you say something we don't like, we can fire you."

CMK: It was just a warning, right? They weren't going to ask you to apologize or anything.

WM: But you know how HR works, right? You say (something happened) "one time," then something else happens, and then something else happens. You know, you have to say, "Well, we're thinking about getting rid of this person. So we have to start working on it."

CMK: They're building the paperwork, the Walter paperwork.

WM: Exactly. They can't just fire you like that. They have to call me. They have to talk to me about it in order to fire me.

Now listen, they might not have ever fired me, but I can't work in a writers' room where people are so sensitive that if I say something just explaining an experience, that they're going to snitch on me.

I couldn't work in the room anymore anyway. My freedom of expression was gone.

And believe me, I don't just think this is true in (the) writers' room. I think that anywhere — if somebody is talking, telling a story, responding to stimulus in the world around them — we have to at least consider the freedom of expression. Does me being uncomfortable mean you lose your constitutional rights? That's an important question.

I know what the Constitution says. I can't yell fire in a crowded theater. I can't use language to attack, bully, or harass a person. But that doesn't mean I can't use language, and language is open to everybody.

That's part of being an American. A big part of being an American.

CMK: What I don't understand is context. I mean, what if you're writing on the show, and the C-word is a part of what is happening? Maybe you're showing that is wrong inside the show, and that's the way you want to go as writers, right?

WM: Oh, I can write in the script. I just can't say it. Which, by-the-by, is worse than the word.

"N-word" is worse than "nigger." Because "N-word" makes it acceptable, you know? It's never gonna be acceptable to say, "Well that nigger did this," but (to say), "Well, you know, the N-word." Well so that sounds OK, actually. And I don't want it to sound OK. That's why I use the real word, not the hyphenated word.

And of course, a lot of black people will argue, "But what if a white person said it?" And I said that if they said it trying to attack or insult or harass me, that's a problem. But if they said it the way I just said it, I can't get on them. I live in America. No, I wouldn't like it, but there are certain things you have to accept in America.

I'm a black man in America. We are some of the original people in America after the Native Americans. We came way back at the beginning of time. And this is my country. And me and my people are part of the creation of that country. And part of that creation is the Constitution.

CMK: As an artist, how does that make you feel?

WM: I was upset when the person was talking to me on the phone. But later after I quit — and I realized that it's OK that I quit — I felt good being able to have that conversation. Because what's most important is that we discuss who and what we are. So the absolute opposite of human resources — we actually sit and discuss something.

I don't need HR to say, "Well, if you keep on making people uncomfortable, we're going to fire you."

I don't need that. That's not helping me. Nobody learns anything from that.

But if I get to talk to somebody and I say, "Well, I felt this" and they say, "Well, we feel that," then yeah, I'm going to learn something, right?

But this is not about learning something. This is about "obey me," Joseph McCarthy says, "or you're going to go into jail. You're going to lose your job. You're going to be out the country."

I'm like, wow. You feel you can just say this to me, do this to me, and it's OK because those are the rules? You know, this is Hannah Arendt talking about "the banality of evil."

CMK: But as writers, if everyone starts censoring themselves for a politically correct culture, then it diminishes the art.

WM: There's no question about it.

Now listen, all writers' rooms are not like this, but almost all HR rooms are like this. All you need is one person to say, "I felt uncomfortable. I didn't feel safe."

And listen: I'm not saying that's invalid. But how one deals with it becomes the issue.

CMK: I want art — especially with words — to push me. I want to be made uncomfortable. Isn't that the point of good art, of good films, of good TV? It's to push us so that we can grow as a culture. I don't think that's happening right now because people are afraid to even write it.

WM: Listen, you don't want to get back to the place in the 1960s and 1970s and 1980s when all the people in a writers’ room were white men. You don't wanna get to that point.

The room I was sitting in, there were four women in the room. There were three black people in the room. There was an Asian woman, a Native American woman. It was all over the place — that is what we need. We need people to represent.

But at the same time, there's a lot of times I feel uncomfortable with things that people say. But I have to learn how to deal with it, either through discussion or dealing with it myself.

Someone said to me a while ago that we should outlaw the Confederate flag, and I said absolutely not. This is America. We have freedom of expression. If somebody has an American flag in their heart, I don't mind seeing it on their forehead too. It's OK. And that's an important thing for me.

I'm not sitting around arguing that only black people have the right to control a certain arena of language. We all have to deal with language. We all have to deal with discomfort. We all have to learn from that and hopefully get better in dealing with each other.