Photo illustration by Mark Riechers. Original images by R9 Studios (CC BY 2.0) and Giles Watson (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The women of Afghanistan are elected officials, school teachers, actors, TV contest winners, ancient rug weavers, and whisperers of forbidden poetry. The Taliban are starting to put down their thumb. But these women want you to know they are more than the timid victim under a burqa.

Anne Strainchamps (00:15):

It's To the Best of Our Knowledge, I'm Anne Strainchamps. This time, last year, women in Afghanistan could do a lot of things. Teach, practice medicine and law, direct films, perform in public, even star on TV.

Humaira Ghilzai (00:45):

In the past 20 years, one of the things that's been booming in Afghanistan is television. What if the most popular TV shows is just called Afghan Star and it's similar to American Idol?

Speaker 4 (00:58):

[Foreign language 00:00:58].

Anne Strainchamps (01:06):

This is Humaira Ghilzai.

Humaira Ghilzai (01:10):

There are performers that come from all over Afghanistan, men and women. Of course, there are judges that critique what they're doing and then at the end, there's a winner.

Speaker 4 (01:27):

[Foreighn language 00:01:27].

Speaker 5 (01:28):

[Foreign language 00:01:28].

Speaker 4 (01:34):

[Foreign language 00:01:34].

Humaira Ghilzai (01:43):

There was a Pashtun woman who was singing and she was very, very popular. She was from Khandahar.

Humaira Ghilzai (01:50):

(singing).

Humaira Ghilzai (02:01):

And when they were interviewing her, she said that she knows that the Taliban vote for her because she dressed very conservatively and she didn't dance while we sang.

Humaira Ghilzai (02:16):

(singing).

Humaira Ghilzai (02:16):

So I would say Afghan Star has produced a lot of star since its inception.

Anne Strainchamps (02:21):

But where will those stars be a year from now? Because in Afghanistan, everything is changing. The new government is widely expected to place severe restrictions on girls, women, and musicians.

Humaira Ghilzai (02:48):

I would think that there won't be any concerts that people can attend to. Maybe there'll be some speakeasy music performances and such, people will probably go in hiding. I know through other musician friends, that people were breaking their instruments, like their beautiful cherished instruments and burning them. So they wouldn't be caught with it. It's very, very sad. It's like the Gestapo coming, everybody's expecting them to come eventually.

Anne Strainchamps (03:23):

Humaira Ghilzai was born and raised in Afghanistan. Her family fled during the Russian invasion in 1976. Today she's a cultural ambassador and co-founder of the nonprofit Afghan Friends Network, which among other things runs two schools for girls in the Ghazni Province. When Charles Monroe Cain talked with her a few days ago, she said that while it's not clear exactly what kind of cultural restrictions the new Taliban government will put in place, things are not looking good for girls and women.

Humaira Ghilzai (03:58):

The schools that we started in rural province has not been reopened. The teachers have been told to not go to school and open it and teach students. Women have been asked not to go to the Teacher Training Institute. So things are starting to really change and I think we will see it unfolding in front of us.

Charles Monroe-Kane (04:24):

You touched on something I wanted to ask about and that you actually run a school in Ghazni Province through your organization, Afghan Friends Network. And you told me that the woman who is the director, she's gone, she feared for her life. She ran that school since 2006 and now, boom, she has to leave the country. Is it that serious?

Humaira Ghilzai (04:46):

Well in her case, she was not only the director of the school, but she was a very vocal advocate of women's rights. She also advocated for women to take a role in the elections, she was voted as a representative to go into the loya jirga in Kabul and represent the women from her area when they were writing the constitution, which was in 2003. So she's been a known commodity and she has been receiving night letters and threats from the Taliban for a long time. So her husband and she decided that now is the time that she should leave because they just felt that the Taliban we're soon going to be encroaching in to people's homes and finding people who had been advocates and known for promoting things that weren't necessarily in line with the Taliban. Her husband and children have been left behind in Kabul and we're hoping that we can help them get out.

Charles Monroe-Kane (05:59):

I want to read something to you, this was Suhail Shaheen. He's the spokesperson for the Taliban. He was speaking to NPR, Steve Inskeep. And this is from the 18th of August. And Steve Inskeep asked him when you brought this up, "If women who are elected, where they relied to stay?" This is what the spokesperson for the Taliban said on the 18th of August and I quote, "Yes, women, the women, they have a right to education and to work and they can hold different positions in jobs right now. The doctors who have started serving, the teachers who have started teaching, also other fields, the women they are working, the journalist women, they have started working by observing Hijab. So yes, women can do their job only if they observe Hijab." That seems like he's like, "Yeah, everything's fine." What do you think of that kind of quote?

Humaira Ghilzai (06:48):

Well, when you're talking about the Taliban, we Afghans are always saying, "Who are you talking about?"

Charles Monroe-Kane (06:54):

Who are you talking about?

Humaira Ghilzai (06:57):

Yeah. So there's the Afghan Taliban, which even today, this morning, my colleague who I was talking to is saying, "They're kinder, gentler people and they care about the Afghan people." Then there's the Pakistani Taliban who is very influential in Afghanistan and there's a large percentage of them that are within this fighting force. And they're basically representing the mission of ISI, that intelligence service of Pakistan and not the peace for Afghanistan. And then there's a third set of Taliban who are currently with this group that has taken over, which is Chechens, Somalis, a lot of people from other countries that are there and we on the outside really don't even know what their motivation is other than bringing some kind of Wahhabi, very conservative type of Islam. So the people that you are seeing as representing the Taliban, I always encourage people to say, "Who are they? Who's doing the fighting, who's mandating these rules? How is Pakistan affecting all of this?" It's a very complicated situation, which is really hard to decipher right away. I think it's going to take some time to really see people's real intentions and motives.

Charles Monroe-Kane (08:26):

That sounds terrible to me. You don't know who your rulers really are, you don't know, quote unquote, who the enemy is. You certainly don't know what's going to change. What's not going to change. You can be punished for something even though you don't even know what the rules are. That kind of anarchy and chaos is just stressful. And I wonder, what's the outlet then? If you're a musician, if you're an artist and you're a woman, what is it that you do or just don't do anything? See what happens?

Humaira Ghilzai (08:53):

Well, it's debilitating, it really is. I mean, some of my colleagues are having anxiety attacks, they are homebound completely unsure of which family member might get hurt in just crossfire or if some buddy's going to attack them, if their neighbors going to report them for something. I have to say very prominent directors, female film directors, such as Roya Sadat, Sahraa Karimi and Shabbat, they all got out of Afghanistan. They are prominent advocates for women and beautiful work and they're not able to continue their work in Afghanistan. I think a lot of people have gone underground, but I can tell you that the amount of anxiety and frustration and sadness and shame I have been feeling here in San Francisco, there's is at least a thousand fold more, maybe not the shame part because as an American, I'm very ashamed of what has happened to the Afghan people. But the fear, because my family escaped Afghanistan when the Russians invaded and we still carry that in our body. We carry that trauma.

Charles Monroe-Kane (10:18):

The school you ran it's closed right now?

Humaira Ghilzai (10:24):

Yeah. And Charles, I feel so sad for our students. I mean, these girls worked so hard, they would come to school early in the morning, they would stay late. They would offer to help in the school to upkeep, the parents would come, the fathers would fix the roof. And when the Taliban came in the province to take over, I mean, they were fighting on the roofs of our school. All the windows have been shattered, their bullet pockmarks on all the walls, all the posters, we had of poets and scientists and such have been ripped and torn apart. My heart really breaks for these girls who really thought education... And even boys, boys were working hard too, that education was going to be their way to a better life, to improve their communities and such. And that is all at this point in great jeopardy and possibly not going to happen.

Charles Monroe-Kane (11:32):

I'm sorry. I just want to say that at this moment.

Humaira Ghilzai (11:35):

Thank you.

Charles Monroe-Kane (11:36):

I'm sorry. I think what's important as you're talking to realize for me, is that you were a refugee, you were a refugee. You came to America via Germany and Pakistan for years in refugee camps and you end up in America. There are a lot of Afghan families who are on the same journey you were on. What advice would you give to them?

Humaira Ghilzai (12:00):

Well, I came here as a child. So my parents experienced what the adults of these refugees are going to face and I want to tell them to hang in there, because the first years are going to be hard. They have to learn the language, I know some of them are translators, but the wives may not speak English, their children may not speak English. If their parents came with them, they may not speak English. So there's the language, there's the whole idea of that you were somebody in your previous country and you're nobody here. You have to start completely from scratch. Everything you have done and built is erased overnight and here you are with what is the knowledge in your head and what you have in your suitcases. So I would say... But don't lose your pride, don't lose your dignity, don't lose hope. Because I think if you have that integrity and that hope that you are somebody that even on those days where you walk into a grocery store and you have $10 in your pocket and you have to buy food for your family, which is what my parents had to do, ration our food, electricity and such, you still bring that humanity with you from Afghanistan. And that should not be forgotten.

Humaira Ghilzai (13:25):

And that even though they have lost everything, that they are not devalued as a person and I think that that is something that a lot of immigrants struggle with.

Charles Monroe-Kane (13:37):

I have one last question for you and because I've been thinking about her a lot. So the woman who ran your school, you guys talk all the time? You said like, what would be the decision to go back?

Humaira Ghilzai (13:51):

To Afghanistan?

Charles Monroe-Kane (13:52):

Yeah. When will she go back?

Humaira Ghilzai (13:54):

She's not going back. No, she is at Afghan Friends Network. We're trying to raise money to help her bring her family out. They will probably be in Turkey for a while and we are working with her to either get asylum for her in Canada or the United States, because what she has decided, despite the fact that she was a prominent figure and her husband is a doctor, that they will have to sacrifice their careers in such in order to have a future for their kids. And that is the decision that my parents also made is to sacrifice everything they had worked for and left their home and everything in Afghanistan in order to make a better life. And I so deeply respect her for this, but I deeply fear for her because I know what compromises my parents made when they came here and started a life again. So she has a long road ahead of her.

Anne Strainchamps (15:09):

Humaira Ghilzai speaking with Charles Monroe Cain. She's the co-founder of the nonprofit Afghan Friends Network. The last we heard about that endangered school director, the US State Department has not responded in any way to her application for refugee status. And as for her husband and children, they can't leave Afghanistan without visas and the foreign embassies are still closed. Humaira is looking for ways to help. Coming up, for most women, leaving Afghanistan is not a choice, especially in the rural areas where wars have come and gone for centuries and the patterns of life can seem unchanging.

Anne Strainchamps (16:12):

A deep breath and suddenly I pictured us the way a bird would see us, a white dove cast of course or a Demoiselles crane, perhaps halfway on it's hallowed and time and again, desecrated migration across the big slate sky. Two people working, a woman carrying food, an importunate visitor, and an old man barefoot in his black galoshes. His glasses held on his head by string. His Soviet shotgun, a poor match for the war around him. Five tiny and fragile figures in the sodden desert, a poor man's carpet decocted out of an eternity of violence and generosity and grace, each of us flawed and so complete. All of us moving into a time warp name Oqa.

Anne Strainchamps (17:22):

Live among the women rug weavers in the village called Oqa, next. This is to The Best of Our Knowledge from Wisconsin Public Radio and PRX.

Anne Strainchamps (17:43):

In 2011, journalists Anna Badkhen spent the better part of a year in an unmapped Afghan village called Oqa. More women and children practice a tradition nearly as old as history, carpet weaving. And I want to go back to the conversation Anna Batkhen had with Steve Paulson, because the vast majority of Atkins live in remote, rural areas, places like Oqa, where foreign wars and invasions have come and gone. While Anna was there, women sat in mud huts weaving while American fighter jets passed overhead. That juxtaposition of beauty and violence as what she tried to capture in her book, The world is a Carpet.

Anna Badkhen (18:24):

Any a rug merchant in the Khorasan will tell you two factors determine the beauty of a carpet. One is the density of its knots. An experienced carpet dealer will count the knots by ear running his fingernail across the hard ridges on the reverse side of the rug. The higher the pitch of the scraping sound, the finer, the yarn, the closer together the knots, the longer the carpet will retain the luscious bounds of its pile. The dealer also might fold the carpet and press on the fold, the wall of a tightly woven carpet will spring back after the rug is unfolded leaving no sign of a crease. Designs are plenty, but which design a customer finds attractive is only a matter of taste of subjective preference. True beauty on the other hand is indisputable.

Steve Paulson (19:16):

That is wonderful, thank you. The one thing that I found fascinating in your description of the making of these carpets is, is perfection is not actually that highly valued. In fact, one of the signs that these are handmade is that there are flaws in the carpets.

Anna Badkhen (19:33):

Well, first of all, in the Muslim tradition, perfection, man-made perfection offense, the omnipotence of God. So perfection is not allowed in a carpet and sometimes a weaver will on-purpose weave a mistake into her carpet. That usually is not necessary because a carpet takes on the shape and the life of a weaver because it's woven over a long period of time between four and nine months. And so there will be a moment when the weaver is distracted because a goat had stumbled into or onto her loom and she has to stand up and get the goat away. Or for example, our neighbor came in and started gossiping and the weaver started laughing and forgot the count of thread and had accidentally woven an extra pedal into a stylized almond tree and so on and so forth. So each carpet is unique and becomes the diary of the carpet weaver.

Steve Paulson (20:42):

The woman who you focus on, the particular weaver is named [Thaura 00:20:47]. What was she like?

Anna Badkhen (20:49):

Very taciturn young woman in her early 30's, probably because most Afghans who are illiterate and most Afghans are illiterate very rarely know how old they are, who wants to count the seasons of privation? Very quiet most of the time, but very open to sex gossip and giggles a lot when somebody comes in and tells her dirty jokes. She is a mother now of three children, she is one of the few women in Oqa who does not take opium as a palliative because her father-in-law forbids it.

Steve Paulson (21:29):

So opium is widespread in this village?

Anna Badkhen (21:32):

Opium is omnipresent in this village because there is no other way to keep aches and pains at bay. There are no doctors nearby, there are no clinics, there are no pharmacies. So the only thing that you can use when you have a backache and you almost always have a backache if you live in Oqa or a stomachache, you take a little bit of opium. If your child is crying because he's hungry or his teething, you give him or her a little bit of opium. If you're pregnant and you have a backache and you feel nauseous, you take a little bit of opium so you're exposing your child to opium prenatally. So basically it's a village of addicts.

Steve Paulson (22:22):

Wow. And also a village that makes extraordinary carpets.

Anna Badkhen (22:27):

It's a village of people who tell amazing stories, it's a village of people who are extraordinary hosts. It's a village of people who are probably sinners and some are magnanimous and some on greedy and some probably are thieves. And it's a village that is a sliver of humanity, it's a village of people just like us, just in different circumstances.

Steve Paulson (22:56):

How did [Thaura 00:22:57] learn to make carpets?

Anna Badkhen (22:59):

She doesn't remember. Her daughter, Layla who was five or four years old when I was in the village was already helping her weave. So probably [Thaura 00:23:13] was four or five years old when she was helping her mother weave. And her mother probably was four or five years old when she was helping her mother weave. This is how the craft is passed down.

Steve Paulson (23:25):

This is a very poor village and the families who make these carpets earn something like 40 cents a day. And then by the time they get to the United States, they sell for thousands of dollars, right?

Anna Badkhen (23:39):

Carpets that are exported out of Afghanistan can travel either west to Istanbul or east, to Islamabad or Peshawar in Pakistan, or they can fly out of Kabul, south to Dubai. And that is where they become extraordinarily expensive.

Steve Paulson (24:05):

How much are they sold for?

Anna Badkhen (24:07):

Here in the states, between 5,000 and $20,000 per carpet?

Steve Paulson (24:10):

Wow. Which makes you wish that the women who actually make them made more money.

Anna Badkhen (24:19):

A lot of things make me wish that women who make carpets made more money, not just the price, the exuberant extortionist price of carpets that people pay for them here but also the fact that oh, I wish for these women healthy children who don't die of common cold that goes untreated and then become something worse. I wish for these women stomachs that are not so empty, I wish for these women ibuprofen when they have a headache, a warm pair of socks in the winter.

Steve Paulson (24:57):

Yeah. Did you feel like your job was essentially bearing witness? You were the person giving testimony of how these people are living.

Anna Badkhen (25:10):

You were saved, not in order to live, you have little time, you must give testimony. That's a poem from a poem by Zbigniew Herbert, a Polish poet, that my lodestar, I guess that that's also how I comfort myself, when I feel very upset with how little I can do. I'm a storyteller and I think that the idealist in me believes that somehow my storytelling can make the world a little closer.

Anne Strainchamps (25:54):

Anna Badkhen, talking with Steve Paulson back in 2013. Her book about the women weavers of Oqa is called The World is a Carpet. And her most recent book is Bright, Unbearable Reality, migration as seen from above.

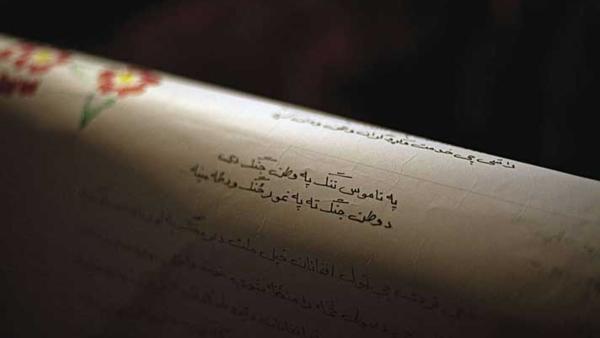

Liza Griswold (26:20):

So I want to tell you about an Afghan girl, a teenager who called herself Rahila Moska. She lived in Helmand, the former Taliban stronghold. Like many young and rural Afghan women, she wasn't allowed to go to school or even leave home but she did find a voice as a poet. Here's one.

Liza Griswold (26:42):

"I call your stone. One day you'll look and find I'm gone." Moska wrote landai, an incredibly ancient form of spoken word poetry, widely shared among Pashtun women, often in secret, and as a way to express forbidden thoughts and feelings. On the day Moska's brothers discovered her poetry, they beat her very badly. In retaliation, she set herself on fire and she died. And Moska's story and poetry would have died with her if it weren't for the American journalist and poet, Eliza Griswold, and her collection of contemporary Afghan landai, called I am the Beggar of The World.

Liza Griswold (27:33):

Landai means a short, poisonous snake. And this form, the landai is spoken by women for women, it's transmitted ear to ear, voice to voice and has been over millennia and it's very subversive. The things that women speak about the issues of sex, war, longing, grief, separation are issues that they're really not allowed to talk about in day-to-day life. And so the landai, because it's collective, because it's anonymous and because it's oral allows women to share their inner most sentiments and disown them at the same time. For example, Rahila Musqa, the young woman who was killed could utter that landai, because she could say, "Well, that's not my poem." And although after her death, her father destroyed the notebooks that survived her, he was unable to kill or to wipe out a poem that was an oral tradition and had been passed among women for centuries.

Anne Strainchamps (28:41):

Any other poetic form anywhere that is almost exclusive to women?

Liza Griswold (28:45):

I think that's exactly right and one reason women have particular purchase over the form of landai, is because of course the women who are speaking these poems are largely illiterate. They can't read and write and the landai becomes as it did for Rahila Moska, an ongoing form of education and a way of speaking when there was no other form allowed to her.

Anne Strainchamps (29:10):

They're so compact. I mean, these are like haikus in a way, but they're dense with emotion. And I wanted to ask you about some that seemed to be love poems to American soldiers or actually they're more like, love-hate poems. So there's one, for instance, "My lover is fair as an American soldier can be. To him, I like dark as a Talib, so he martyred me." Wow.

Liza Griswold (29:36):

Yeah. Now that's an old one. And it used to say, "My love is fair as a British soldier can be." Because it is a tacit criticism of occupation. And of course, long before the Americans set foot in Afghanistan, there was the 19th century British occupation.

Anne Strainchamps (29:57):

So there's this sense in which the soldiers are simply interchangeable. It's one more occupation for this-

Liza Griswold (30:01):

Oh, absolutely. The soldiers are interchangeable, occupation is interchangeable, the enemy is interchangeable. And yet the idea of being misread, misunderstood, seen in a mistake informed that the outsider is so blind to Afghan life, that he will not understand or recognize his own lover. That's what stands at the heart of that poem.

Anne Strainchamps (30:28):

There are also some really chilling anti-American poems. There's one, I couldn't get it out of my head. Wait, let me find it. Oh, yeah. So this one's written by a mother. "My Nabi was shot down by a drone. May God destroy your sons America, you murdered my own."

Liza Griswold (30:47):

Yes. The name of this mother was Chandana, and she did not sing this foam to me directly. This was repeated to me by her cousin. So she never would have written this poem because she cannot write. So this is just an oral tradition and she would sing this. She did sing this at a wedding and men and women are segregated for weddings as they would be for any ceremony in Afghan society. And so in a women's wedding, typically at henna night, before she's married, when the bride is decorated with henna on her hands and feet, women sing landais. They sing them with a small hand drum called a [daria 00:31:29]. And yes, this mother to her understanding, he was killed by a drone. Now, does she know that for sure? No way, but the drones, drones are very prevalent in Afghan society now in both the common consciousness and the rage against ongoing occupation but also in the landais, which was shocking to me that they'd entered the language of the landais themselves.

Anne Strainchamps (31:55):

Also some of these seem to be supportive of the Talibs, but then others aren't. There's one, "May God destroy the Taliban and end their wars. They've made Afghan women widows and whores."

Liza Griswold (32:10):

Mm-hmm (affirmative). There's absolutely rage. There's rage against all forms of oppression in these poems and the Taliban, they're not popular. People join... Here's what happens in a village and this is why women sing about the Taliban with such disgust. In a village, the Taliban will come through and demand that a family give over one of their sons. And so that leads to rage because in the same way that Chandana would sing about her rage at the Americans for killing her son Nabi, she would sing about her rage at the Taliban for taking one of her sons for their ranks as well. And moreover, because women have suffered so much under the rule of the Taliban regime, which still rules and has parallel governments in much of rural Afghanistan today, the hypocrisy of the religiosity of the Taliban, and yet the way in which when they were in power, they abused women. That really is a common theme of both women's talking to one another, but of course of the landais as well.

Anne Strainchamps (33:28):

You know, one of the things that's really interesting to me is, the women's voices as they come out of these are so powerful. I mean, they just the page at you. And these are not the voices of shy or modest or humble women. Did that surprise you?

Liza Griswold (33:49):

It did and it didn't. I mean, because I've been working in Afghanistan for more than a decade on and off, I had some sense of the volubility, the rage, the earthiness that with which many Afghan women speak all the time. And as I wear a couple of hats as a journalist and a poet and so I love looking at the edges of society, for both me and for the photographer, Seamus Murphy, with whom I was working, who's worked in Afghanistan for 25 years. One of the things we wanted to do is explode the image that we have in the West of an Afghan woman being a mute ghost beneath a blue burka because she is anything but, and the frankness with which women speak is woefully under reported because there's not much space for it in the news headlines. So what we were trying to do, is get beyond those headlines and let these women speak for themselves.

Anne Strainchamps (34:55):

And yet at the same time, they may have strong voices. But so many of these poems are about their oppression, the really heartbreaking ones to me often are young girls who clearly are being married against their will. Oh, what's the one, there's something about. "I dropped the spinach on the-

Liza Griswold (35:16):

Oh, yeah.

Anne Strainchamps (35:18):

How does that one?

Liza Griswold (35:19):

Got that. That one goes, "Today, I dropped the spinach on the floor. Now the old goat stands in the corner swinging a two by four."

Anne Strainchamps (35:32):

Is there a landai you would leave us with?

Liza Griswold (35:35):

Sure. "When sister sit together, they're always praising their brothers. When brothers sit together, they are selling their sisters to others."

Anne Strainchamps (35:55):

Poet and journalists, Eliza Griswold. Her collection of Afghan women's poetry is called I am The Beggar of The World. And we were talking shortly before it came out, back in 2014. But I wanted to revisit our conversation today because with the Taliban back in power, listening to and cherishing the voices of Afghan women is more vital than ever. So we're talking about sisterhood, the sour between Afghan women and Western women and how have we in this country measured up as sisters? Not well, according to my next guest. Do you think feminism was invoked in order to build support for the war and that American mainstream feminists were basically duped into supporting it?

Rafia Zakaria (36:45):

Yes.

Anne Strainchamps (36:47):

Stay with us. I'm Anne Strainchamps and this is To The Best of Our Knowledge from Wisconsin, public radio and PRX.

Anne Strainchamps (37:03):

Feminism should mean women supporting each other across cultures and continents, right? A global sisterhood. Except that some of us have not been very good sisters. That's the message of Rafia Zakaria's new book Against White Feminism. Zakaria is an author, an attorney and human rights advocate. She grew up in Pakistan and she served on the Board of Directors of Amnesty International and lately, she's been thinking about the day in 2001 when Colin Powell announced American invasion plans with the backing of a group of prominent American feminists. And that's why Zakaria calls it the First Feminist War.

Rafia Zakaria (37:47):

That was probably one of the first times in modern history that the feminist movement, the US or Western feminist movement, instead of serving as a check on state power, as it had, even in previous wars like Vietnam, essentially allied itself with the war project. So all these women, all these American women, Hillary Clinton and Madeline Albright, Laura Bush, even Gloria Steinem supported this action. Even though at that time, there were indigenous Afghan feminists on the ground who were very, very against occupation and the invasion and were arguing for peace.

Anne Strainchamps (38:36):

Well, I mean, the idea at the time was that women and girls in Afghanistan were living under oppressive conditions and that getting rid of the Taliban would not only strike a blow against terrorism, it would also open the door to more rights for those women like education in a country in which what, 30% of the women are illiterate? And jobs and the right to self-determination. So what's wrong with that argument?

Rafia Zakaria (39:01):

What was wrong was you can not simultaneously bomb a country into the stone age and then also say you're going to empower and uplift its women. That's one society, women and men don't form a separate society anywhere. The problem with the goals was that they were used as window dressing to hide the mayhem and the night raids, home raids, people being dragged away for months, no one knowing where the father or the brother has been taken. Just extremely intrusive and demeaning tactics used by the US military who was fighting a war in Afghanistan. The consequence of that, is that those good goals, whether it's education or empowerment or job training, they become de-legitimized because they're attached to this very painful and derogatory foreign occupation.

Anne Strainchamps (40:13):

Do you think feminism was invoked cynically, deliberately by the administration in the military in order to build support for the war and that American mainstream feminists were basically duped into supporting it?

Rafia Zakaria (40:27):

Yes. And I understand the temptation because essentially, American feminists had the outset of the war were told that, "Look, you guys are feminists. You guys are strong, you guys are empowered and we're going to export you and your greatness to this environment where women are oppressed." And this narrative was a very, very convincing and very, very a narrative that essentially placed the United States on high moral ground. Even though, I mean it was repeating a very colonial message of white men going and saving brown women from brown men, which is the famous adage.

Anne Strainchamps (41:16):

Well, we should talk about Zero Dark 30. The movie came out in 2012. It's a fictionalized story about the CIA agent who was involved in the hunt for bin Laden. But you tell just a riveting and an actually really painful story about watching it. What was that like?

Rafia Zakaria (41:35):

Yeah. I went to watch the movie, I was in Indiana at the time and it was the most isolating and just emotionally wrenching moment, because the entire dramatization of that movie is around this idea that a strong woman, undoubtedly a feminist woman, is one who is willing to torture and hurt men who look like my father and my brother and all of my family. I was watching this movie against a larger environment in the United States where my brother himself had been questioned by the FBI for no reason whatsoever. And I knew a lot of other people who were in a similar position. So watching Americans uncritically embrace and digest this person, the CIA agent who it's like, there's a famous line in that movie even they first hear of the girl, "She's a killer." And being a killer was supposed to be this ennobling thing and I saw in that movie and its reception, almost like a culmination of what the Bush Administration had commenced.

Anne Strainchamps (43:03):

As the coalition force occupation went on and the whole humanitarian aid project really ramped up in Afghanistan, we began seeing more and more stories about shelters for women and schools for girls and women getting jobs in government. Pragmatically, did women's lives improve?

Rafia Zakaria (43:27):

Look, I won't lie that as a feminist myself, I'm not from Afghanistan, but neighboring Pakistan and this is typical of a lot of projects that try to empower women. So in the short run, yes, there is an improvement, right? There are women in government, there are more women working, there are more universities and schools open, but because this was such a top down thing, right? Where the money was coming externally, there was really no cultural or political buy-in to the increased presence of women. It was essentially a gamble that, "Okay, let's just get women in these roles and once they're in these roles, that might foment some kind of a cultural transformation and social transformation in Afghanistan." And of course, the events of the past couple of months have shown that that's not true.

Anne Strainchamps (44:30):

Well, you're talking about the dangers of trickle-down feminism? You're phrase, this idea that what women everywhere in every country need is the kind of life that middle to upper middle-class white women have, a world in which every woman wants a career and a glass ceiling to bust.

Rafia Zakaria (44:51):

That's exactly right and that was the core kernel trickle-down feminism was how women's empowerment within Afghanistan basically failed.

Anne Strainchamps (45:05):

How much of this do you think goes back to colonialism, which seems to have left its sticky traces on everything?

Rafia Zakaria (45:14):

Oh, I mean, yes. The book starts from the colonial era for that reason. For instance, I present the example of Gertrude Bell, this British woman who goes out to the Middle East at a time when the British Empire has essentially conquered all of the Middle East. And she goes saying, "I'm a person in this world, I'm a person in this world." Which what she means is she doesn't even have the vote back home in London, but she goes to Jerusalem and to Haifa and over there being a white woman, means you're still above brown men. And so there's this immediate racial privilege that is accrued to you and you see the same tropes repeated in Iraq and Afghanistan, where white female journalists from the United States, a New York Times journalists went out there. And of course, yes, they are above brown women and brown men in that society. And so you have them exercising their white privilege in careerist ways, such that they appear feminist heroines to the women back home, but they're really part of an oppressive racial hierarchy.

Anne Strainchamps (46:36):

Let's just tease that out just a little bit because it's not immediately obvious to me. And I'm not sure that I would agree with you that all these women were reporters and journalists went out in a blatantly careerist way. It seems to me that it's more like they went and profiled girls going to secret girls schools and women running book clubs. They used their gender as a way in with the intention probably good intentions, of simply telling women's stories. But the question is, when does telling somebody's story becomes using somebody's story?

Rafia Zakaria (47:14):

The point when it becomes predatory, is that in a lot of cases, the women that they were writing about stood to be actually physically harmed from the story. So for instance, Linsey Addario, the Pulitzer Prize winning photographer, right? When she talks about going into a secret school, hiding from the Taliban and she takes pictures of those girls, she's endangering those girls, because that's the whole point of the secret school, right? It's exists so that the identities of those women won't be known and they can continue to operate this school. So when you take that picture and it's published in the New York Times, it's obviously no longer secret but nobody even considered that in that story. And it's that part to me that is disappointing.

Anne Strainchamps (48:15):

And that's where the legacy as a kind of Victorian patronizing benevolence comes in? It's like, "As long as it seems like we're motivated by humanitarian reasons, it can be easy to treat the people you're trying to help as victims and assume that what's going to be good for them."

Rafia Zakaria (48:36):

It's important to recognize that white feminism gets some of its self-righteousness from presenting that contrast between the white woman as progressive, forward-looking pioneering and all other women as oppressed and far, far behind in their journeys to feminism and empowerment. And the fact is that's simply not true. It comes from the colonial era definitely, right? And it's ironic to consider that now for instance, one of the visual comparisons that's always drawn is the burka. These women are covered, the burka, the burka. Back in the Victorian age, women were going to India and they were scandalized by the sarees because they were showing too much flesh, how are you showing your midriff? And this is so bad. It doesn't matter what it is, it becomes a subject of derision because it doesn't accord with the white feminist project of the moment.

Anne Strainchamps (49:50):

So going forward, what would real sisterhood be?

Rafia Zakaria (49:55):

I think real sisterhood would be a very intentional and pointed effort to have these difficult conversations around race, so that we can recognize the real battle, right? The larger battle, which is against patriarchy. I really think that this can be done.

Anne Strainchamps (50:20):

Yeah. I actually think it's a really exciting and potentially transformative time.

Rafia Zakaria (50:24):

I completely agree with you, yes.

Anne Strainchamps (50:35):

Rafia Zakaria is an author and human rights advocate. Her new book is called Against White Feminism.

Anne Strainchamps (50:46):

And that's it for today. This hour of To The Best of Our Knowledge was produced by Charles Monroe-Kane, with help from Shannon Henry Kleiber, Angela Bautista and Mark Riechers. Our technical director is Joe Hartdke, our executive producer is Steve Paulson and I'm Anne Strainchamps. Thanks for listening.

Speaker 12 (51:03):

PRX.