Dutch painter Piet Mondrian said, “The position of the artist is humble. He is essentially a channel.”

But what if the humble artist is an AI robot? What are they channeling?

When poking around with ChatGPT, the chatbot suggested if “To The Best Of Our Knowledge” producer Charles Monroe-Kane wanted to learn about what it would look like for AI and human beings to be creative collaborators, painter Sougwen 愫君 Chung is the person to talk to.

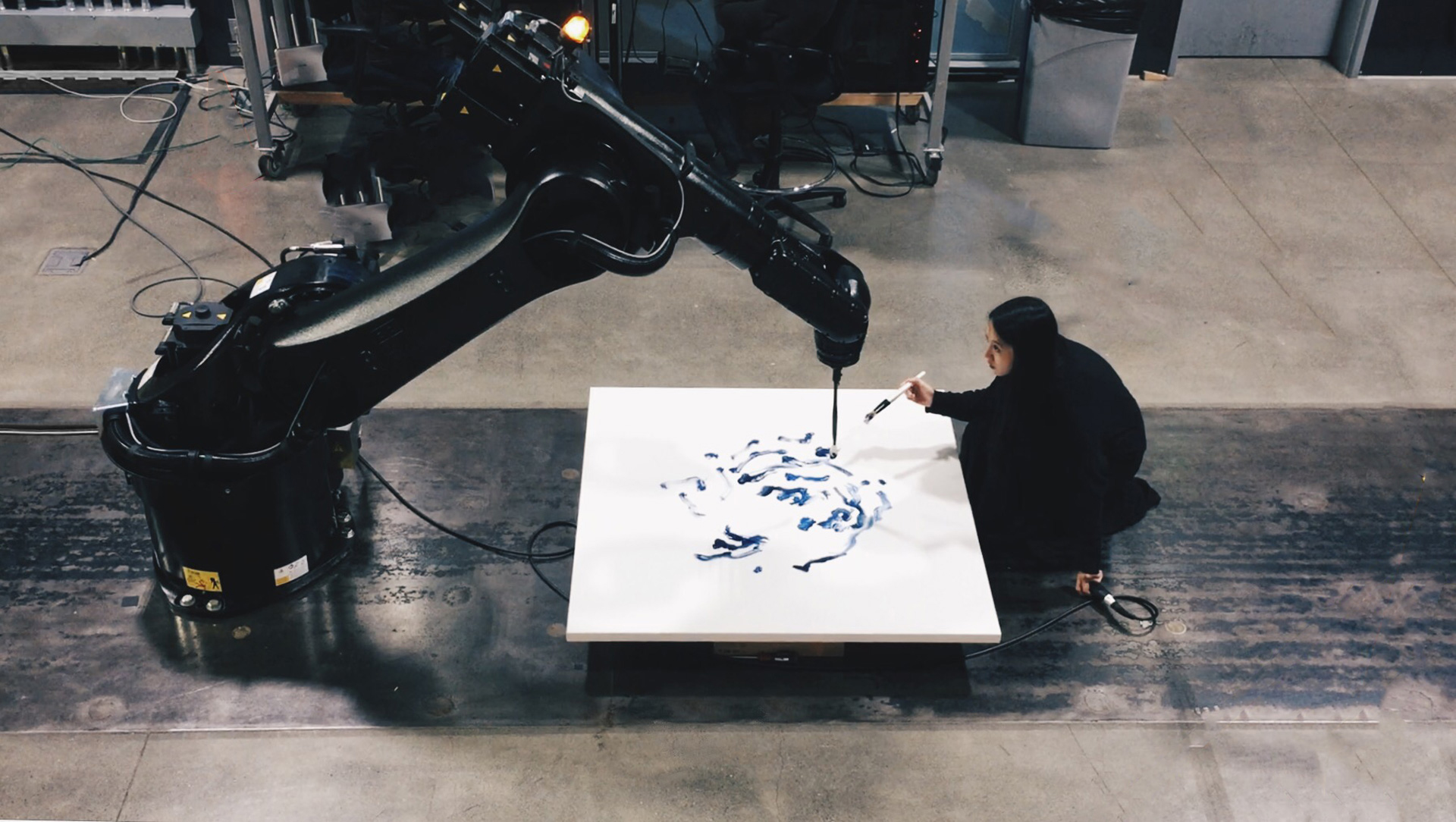

Chung has trained robots to physically paint with her using AI. And when they paint something together — say, a black oil-paint brush stroke — the robot mimics her.

But at some point, the robot continues without Chung and paints something new. And don’t think cold or modernist. The output is organic and beautiful — large canvases filled with abstract flowing lines. Bold and sublime.

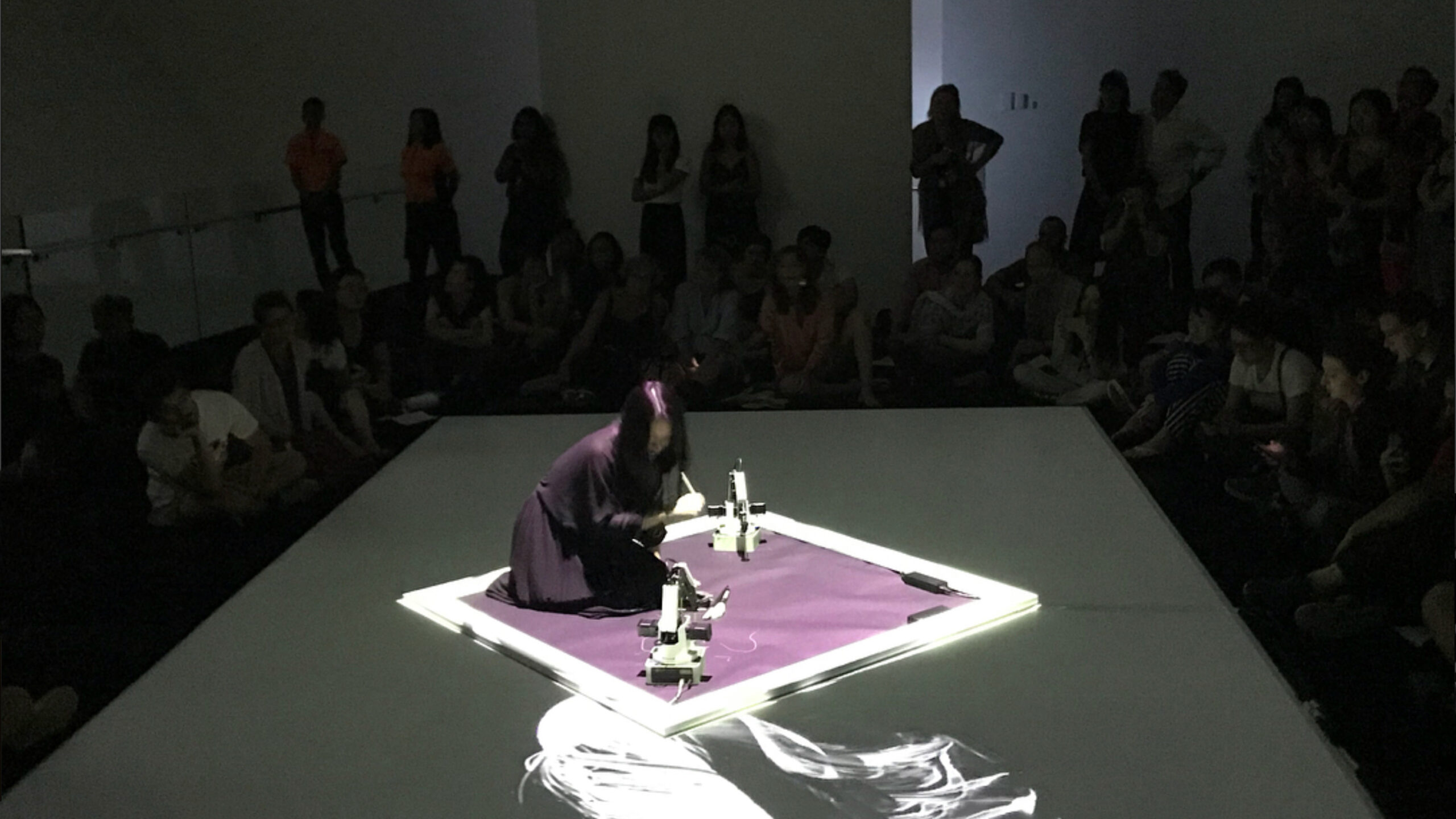

Using an EEG headset, Chung uses her brain waves to communicate with the robots, often in deep meditation and in front of audiences.

Chung is a former fellow of MIT Media Lab and Google Artist in Residence, She was recently named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in AI.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Charles Monroe-Kane: I didn’t know who you were until ChatGPT told me about you. And I went to see your art and I had all these ideas of what it was going to be, and none of those ideas held up when I got to the paintings. They’re beautiful. Is beauty a goal?

SC: I think maybe in a way, beauty is the goal. I think more so than beauty, I like this idea of escaping my own frame of mind, almost like being in a state of flux and a flow state that puts my own conscious mind out of the equation.

I guess because I do many of these paintings as a performance, it’s a lot about trying to navigate that state of attention and presence from other people on the canvas. How that happens is I try to create movements and a balance with the machine system that grounds me and calms me down.

I think if that output resonates with people in the way that they describe it as beautiful, that’s really powerful. It’s not something I’m trying to do at all. But I think it might be a product of my presence with the system potentially.

CMK: I had mentioned earlier that ChatGPT picked you as a guest. Here’s the first question it suggested I ask you: “You embrace imperfection. Would you be disappointed if you and the machine made something perfect?”

SC: I think our idea of perfection is really linked to control, and I personally am not that interested in control. I don’t think that’s where we find it. That’s not where I find moments of inspiration.

If the result of the work is “perfect,” then I think it’s predictable. I think it’s expected. It means we had an idea in our head of what it was, and then it resulted on the canvas. And that’s not, as a painter, something that I get out of bed for. If I already have it in my head, then it kind of exists already.

What I like about the imperfection of the process is there’s real tension. There’s real wayfinding involved.

CMK: There’s this idea called “hallucination” — a machine or AI does something that’s unexpected and doesn’t repeat it again. What do you think of those moments? They seem important to me.

SC: I think what’s really interesting about where we are with these systems is this idea of machine translation and synthesis. When you work with large data sets, like the one that drives ChatGPT or Dall-E or Midjourney or any of these systems, this idea that it’s hallucinating is really powerful. I think it comes from humans anthropomorphizing things, which is really exciting.

I’m not sure if I wonder if that’s unique to our species — the dream of seeing ourselves in other things —whether that’s like our pets or our microwaves or our machines or our cars. I think that mirroring and that echo is really, really fascinating.

I would argue that what these systems allow us to do is sort of hallucinate together in an interesting way. Bringing new images and new ideas out into the world to create a more vivid imagination about what things could be is kind of exciting. So if that’s the outcome of a hallucination, then I’m here for it.

CMK: Here’s another question from ChatGPT: “Do you believe that machines could one day become autonomous creators, or do you believe that they will always require some level of human input or collaboration?”

SC: Given that these systems and machines are built by human beings, as far as I know, I think that always becomes an extension and a creative expression of human intent. So I think in some ways it’s always some additional apparatus for human creative expression, and they will always be inextricably intertwined in a way.

CMK: Is there a moment coming in the future where you come downstairs to the studio and the machine is making art on its own?

SC: Wouldn’t it be funny if I said that I unplug all the robots before I go to bed?

CMK: Do you?

SC: It would be funny if I did.

CMK: Most people, and I mean in the world, certainly in America, they’re afraid of AI. From “Blade Runner” to how Congress talks about it. Why are we afraid? What do you think we’re afraid of?

SC: If we think about machines as human extension in a lot of ways, or manifestations of human intent or extensions of ourselves, there are some dark aspects of humanity that can be extended through the machine apparatus. I think that drives a lot of how we construct this idea of the AI.

But at the same time, there could be just as well machines of care and machines of stewardship and machines that steward nature, that we don’t see as much because we haven’t built them yet.