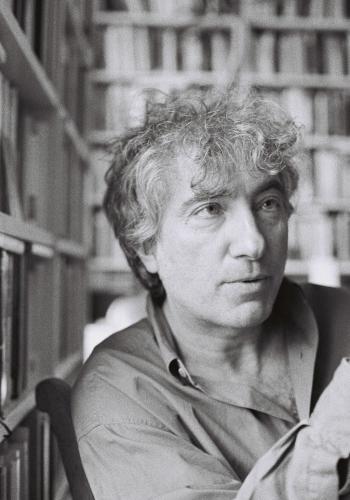

Adam Phillips has made a career out of dissecting the most intimate details of our lives. The British psychoanalyst has written books on monogamy and kindness, even flirtation and kissing.

His latest is titled “On Giving Up.” It’s not what you might expect — a manual for how to push through difficulties and overcome obstacles. Instead, it’s an extended essay on the virtues of letting go of the routines and fixed ideas that shape how we live.

This may mean giving up on a relationship or a job that’s no longer fulfilling, even though the prospect of leaving is scary. For Phillips, giving up is often necessary to open up the space for new possibilities and life directions. It’s also a particular kind of mindset that prizes curiosity and spontaneity — and the willingness to live with uncertainty.

Steve Paulson recently talked with Phillips for “To The Best Of Our Knowledge.”

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Steve Paulson: For most people, I think the idea of giving up is actually kind of shameful. We celebrate people who keep going, especially when it involves sacrifice to do something that’s really hard. Clearly, you have a much more nuanced view. What made you start to think about giving up?

Adam Phillips: Well, partly for the reason you said. There is a great deal of shame attached to it. And it occurred to me that giving up is something we should be able to do in certain situations. If we live in a culture in which persistence and seeing things through and finishing things off is highly valued, it makes giving up extremely difficult.

We all know from experience that clearly some relationships should be given up on, some interests are given up on. Our pleasures change and so on. So I suppose I was interested in the difference between the fact that when we give something up, like chocolate or alcohol, we believe we can change. And when we give up [on giving something up], we believe we can’t.

“I want to differentiate between the real difficulty of mastering something one values and a different kind of difficulty, which is giving up on something one really doesn’t want to do.”

Adam Phillips

SP: You say the question that really interests you is not why do we give up, but why don’t we give up?

AP: Yes. It’s linked in my mind with the way in which some of us are taught to put up with things, to endure, and not to be able to consider whether we are really enjoying something. In some situations, the harder it is, the better it seems to be.

Clearly, you can’t become an athlete or a piano player without going through a great deal of suffering, because these skills require working through resistances. But some resistances mean you actually don’t like something — it’s not for you. I want to differentiate between the real difficulty of mastering something one values and a different kind of difficulty, which is giving up on something one really doesn’t want to do.

I can remember going to my daughter’s parent-teacher meeting and the teacher said to me, “The trouble is that she only works on a subject she’s interested in.” And I thought, good for her.

SP: Let’s talk about what is actually involved in giving up. You say it’s giving up the wanting. Can you explain what you mean?

AP: Yes, you could think what keeps us going is our appetite. We’re going to become hungry in the next hour or so. And of course there are lots of different kinds of appetites. There’s an appetite for safety, there’s an appetite for protection, there’s an appetite for sex. All these appetites are in a sense what fuel us or form us or inspire us.

It seems to me that our relationship to our desire, to our appetite, is very revealing in terms of how much we want to live — whether we want as much pleasure and satisfaction and gratification and enjoyment as we’re able to have, or whether we want as little as possible.

It’s something about people’s relationship to pleasure. The problem with pleasure is that on the one hand, it can be overwhelming, and on the other hand, if someone or something gives us pleasure, we can begin to feel dependent on them or even addicted.

So, pleasure is very problematic. It’s the thing that sustains us, but it’s potentially dangerous. This is something that psychoanalysis has interesting things to say about. We can be as frightened of pleasure as we are of suffering.

SP: It sounds like you’re talking about deprivation. The “not wanting” is putting aside the thing that we actually do want, but we’re going to try to forget about it. My sense is you’re talking about something more profound. To not want is actually to lose that desire in the first place.

AP: Most of the world religions are very often about self-depriving strategies for higher ends, as though there’s something about our animal nature that is a huge problem for us. And to develop, to become enlightened, to grow up — whatever our project is — involves the renunciation of certain pleasures and satisfactions.

Now, having been a child, everybody knows that life is intrinsically very frustrating, but it can be so frustrating that one wants to turn against desiring — or if it’s just the right amount of frustration, then of course that sustains our desire. We go on wanting. If I’m not fed for two weeks, it wouldn’t be odd if I began to lose my appetite, but if I’m fed every other day, I’ll be hungry.

SP: Freud talked about the death instinct, this forbidden attraction to not living anymore. You reframe this as the giving up instinct.

AP: Freud has what is in many ways a very strange idea, which is that our lives are the battle between life instincts and death instincts. There’s a part of ourselves that wants as much life and as much pleasure as we can manage. And there’s a part of ourselves that wants as little life as possible, that wants to anesthetize ourselves, that wants to be more or less dead or as close to dead as we can be — unstimulated but safe.

Now, what Freud is flagging up is the possibility that there is a part of ourselves that really doesn’t want to live, that can’t bear it. And it seems to me everybody who is at all awake has at least had moments or periods in their lives where they felt their lives were actually unbearable.

SP: My sense is that for you, that death instinct is something we can all resonate with at one time or another in our lives. How deeply do you think that cuts for most of us?

AP: I agree with you in the sense that a great deal of work goes into deadening ourselves — to desensitizing ourselves — to other people’s suffering and to our own. So there’s a lot of evidence that we at least intermittently find life unbearable.

Now, if you are not a religious person, the question is: what is the point of suffering? If you are a religious person, there are lots of good stories about why one might and must and should suffer. If you are not a religious person, the question is what is the point of one’s suffering or why go on living one’s life if one’s not enjoying it?

And there are answers. Some of us have children, some of us have responsibilities, some of us want to defend values that seem very important. But on the other hand, it would seem to me there are real grounds in some lives for absolute despair. And I think that has to be part of the conversation. Otherwise, it’s as though we’ve all got to be more or less upbeat and we don’t feel it all the time.

SP: To let in the despair, to acknowledge it and to talk about it. That’s important.

AP: Yes. And to see if anything can be made of it. Not assuming that everything can be transformed into something good and wonderful, but actually seeing where we go with our feelings.

That, in a way, is what psychoanalysis and talking therapy is about, which is finding out what it is you do happen to feel and think, and finding what you can make of it, if anything.

SP: You write about the artist and psychoanalyst Marion Milner, who has a fascinating take on how we think about things like happiness and fulfillment. She had this distinction between what she called “narrow attention” and “wide attention.” Can you explain that?

AP: In narrow attention, it’s as though we know what we’re looking for and we find it if we can. And she talks about it as predatory, or as full of appetite.

Whereas wide-angled attention is almost what it says it is. You look widely without knowing what you are looking for or that you’re looking for anything. Your capacity to be affected and to receive stimuli is wide open.

Marion Milner once said to me, “When I paint a tree in a field, I look at everything but the tree.” In other words, she needed to really open her eyes. And what she’s saying is that we sacrifice a great deal in being focused, in having our attention over-organized.

She doesn’t say one kind of attention is better than the other. She says these two different kinds of attention are better for different things.

SP: But she’s saying that if you’re convinced you know what you want, or what you’re paying attention to, that’s going to narrow how you see the world. Your perceptions will be limited. It’s the opposite of curiosity.

AP: Exactly. What’s being suggested here is that there’s always a temptation to narrow our minds because we are extremely complex and extremely receptive. It creates anxiety in us. And so, if we can find a way of narrowing our minds, it’s as though there’s relief.

But then all we’ve got is a narrowed mind. You can see addiction, for example, as an acute case of this. If I think, “What do I want? I want a cigarette,” it’s as though it has been sorted out. But in the very act of narrowing our minds, of diminishing our complexity, we lose a great deal of other wishes and wants.

“And I think it’s also something to do — strangely or paradoxically — with being able to forget oneself, to be absorbed in other people and other things.”

Adam Phillips

SP: This practice of wide attention is very appealing, but it also seems pretty hard. You’re talking about giving up your certainties, what is familiar in life and embracing the unknown.

AP: Yes. But it could even be — in a small localized way — a very good simple experiment in living.

You literally go outside and don’t focus on anything. You just see what you’ll find yourself noticing if you don’t focus. You allow your attention to drift.

The psychoanalytic version of this is free association, where you don’t speak coherently, you say whatever comes into your mind. And speaking coherently, in a way, is an attempt to protect yourself from all the really enlivening incoherence inside you.

SP: Are you talking about tapping into your unconscious, bypassing the default mode network, that rational part of ourselves?

AP: Yes, or finding a way out of one’s defensive self or one’s self as one would like to see one’s self. It’s very familiar in adolescence, that feeling that one is really in one’s body. And I think it’s also something to do — strangely or paradoxically — with being able to forget oneself, to be absorbed in other people and other things.

When somebody’s anxious or depressed, they are self-obsessed. They have to be, because they’re looking after themselves. I would say the aim of psychoanalysis is to enable people to forget about themselves. Not to become more interested in themselves, but less interested, and therefore more interested in other people and the world.

SP: That’s fascinating. I would’ve guessed that the purpose of psychoanalysis is to know yourself, to gain self-knowledge. But that’s not what you’re saying, is it?

AP: The official story is you need to increase your self-knowledge to have the life you want. Now, in some areas, that seems right, but more prominently, the idea is that you really need to be able to forget yourself in order to engage other people in the world.

This is not a modest comment. I think one is the least interesting person one knows, in actuality.

SP: One point in your book that really struck me is you say that giving up requires a sense of an ending. What’s a good ending?

AP: Well, I think when you feel you’ve completed something to your satisfaction, when you feel it’s necessary now to do something else without feeling you’ve had to sacrifice something in the process.

SP: An ending is not necessarily a sense of completion, it’s something different.

AP: Yes. Something has finished and one now needs to do something else.